TAKE YOUR CARDIO INTO THE “ZONE” –

THE 90-MINUTE PER WEEK ULTIMATE FAT-BURNING WORKOUT

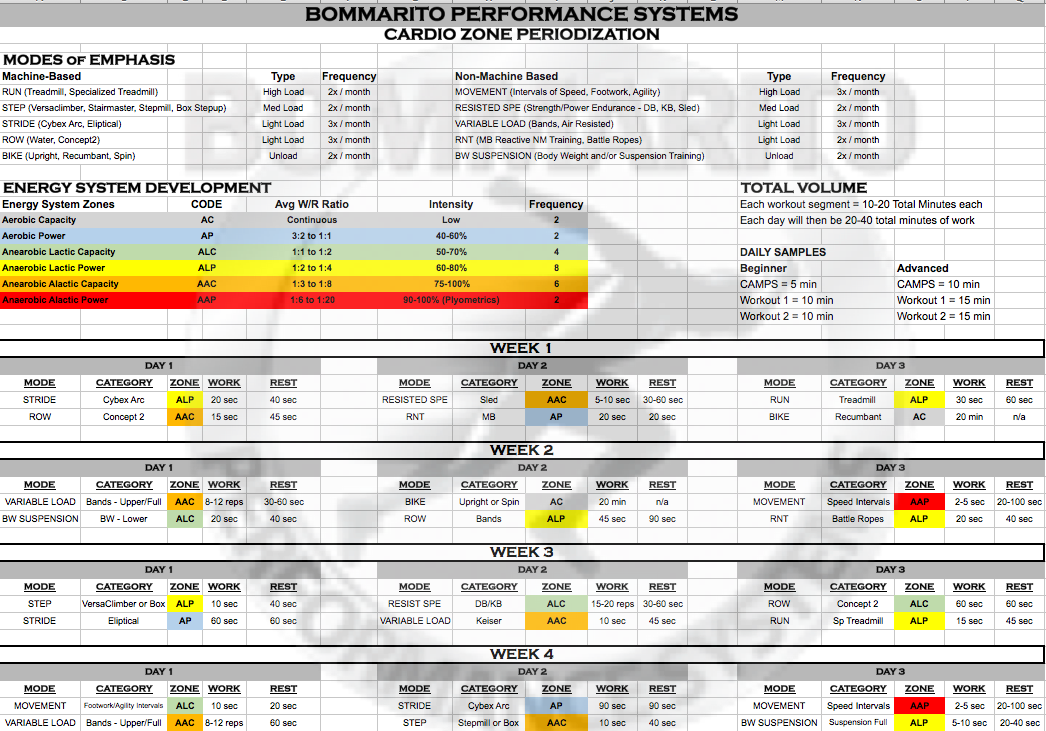

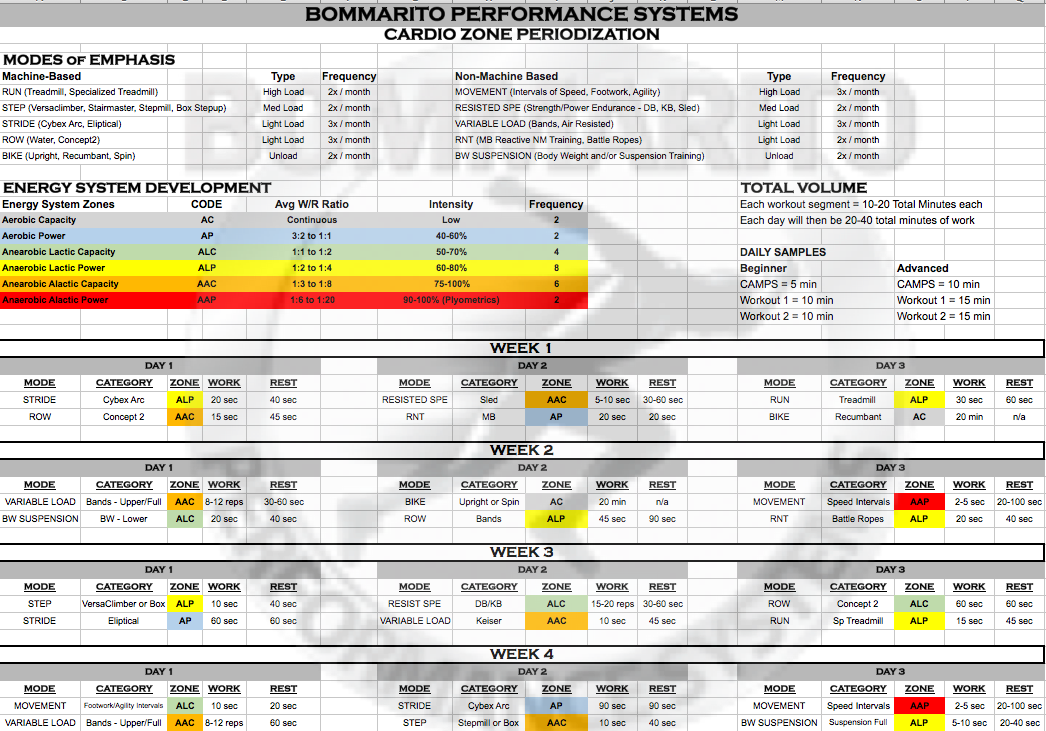

BPS 6-Zone System – The key to maximizing Fat Loss Without Over-Training

Pete Bommarito, MS, CSCS, USAW, MATCS, MAT JS

- Quality over Quantity

- Convenient Training Schedule for Hectic Lifestyle

- Efficient workout that provides most “Bang for Buck”

As trainers, we are constantly fighting logistics. Logistics of how often a client can attend training sessions, the session length, and the maximum intensity that can be sustained each session. Hence, we are always trying to find the most efficiency for the allotted time. Most group fitness classes, Cross-Fit, or even athletic speed/conditioning sessions do a great job of working within a key energy system that make quick gains. However, if you limit your training to one or two energy system zones (even the key zones), you can never make maximal gains; and you will never be as efficient in these key zones. The BPS 6-Zone System allows for ALL of the cardio zones to be taken into account over a training cycle – obviously emphasizing certain zones, but never leaving anything out. This can be implemented into athletic programs or for regular fitness clients or groups. That’s the most intriguing part of this 6-Zone System – it can really apply to any fitness client or group at any level. The difference will be the mode of training or exercise equipment and overall intensity within the session. Also for athletes, the frequency of each zone per month-microcycle can change dependent on the sport and off-season phase.

Looking at the most efficient ways to maximize Cardiovascular Fitness, a full understanding of ALL of the energy systems is crucial. There has been an abundance of research and applied methods that is dedicated to the holy grail of “fat loss” and “toning”. The main thing to think about when breaking down research to put into training protocols is to understand the big picture. Research has led to a number of various concepts such as “High Intensity Interval Training”, “Fat Burning Heart Rate Zones”, “Power Endurance”, etc. All of these are great concepts, but only really work within a limited amount of energy system zones. While all of these concepts are good and effective, a training program can never leave out the big picture – maximize efficiency of ALL of the energy systems in a given microcycle, just have a specific EMPHASIS on a system that is personalized towards the ultimate goal and purpose.

Breakdown of the Energy System Development (ESD) Zones

Aerobic Capacity (AC)

- Average Work:Rest Ratio – None, it’s more of a consistent long slow distance

- Intensity – Low

- With presence of oxygen

- Improve peak oxygen consumption and associated cardiovascular functions to support endurance performance

- Developing the “aerobic base”

Aerobic Power (AP)

- Average Work:Rest Ratio – 3:2 to 1:1

- Intensity – 40-60%

- With presence of oxygen

- Maximize the efficiency of the aerobic base via longer interval training

- Maximizing the efficiency of the base

Anaerobic Lactic Capacity (ALC)

- Average Work:Rest Ratio – 1:1 to 1:2

- Intensity – 50-70%

- Without presence of oxygen

- Lactic – anaerobic glycolysis will be the primary energy source utilized

- The shift of raising the the tolerance to lactic acid accumulation; the beginning of raising the Lactate Threshold (LT)

Anaerobic Lactic Power (ALP)

- Average Work:Rest Ratio – 1:2 to 1:4

- Intensity – 60-80%

- Without presence of oxygen

- Lactic – anaerobic glycolysis will be the primary energy source utilized

- Raising the Anaerobic Threshold (AT) (the point at which lactate is produced faster than it can be removed)

Anaerobic Alactic Capacity (AAC)

- Average Work:Rest Ratio – 1:3 to 1:8

- Intensity – 75-100%

- Without presence of oxygen

- ATP-PC phosphagen systems will be the primary energy source

- Maximize the ability to execute high power output exercises over a set period of time

Anaerobic Alactic Capacity (AAP)

- Average Work:Rest Ratio – 1:6 to 1:20

- Intensity – 90-100%

- Without presence of oxygen

- ATP-PC phosphagen systems will be the primary energy source

- Raise the overall threshold for overall power output

Most people that do endless minutes on cardio machines are working in the AC and AP zones (yes, even if it’s done on the “interval” setting). Most group fitness classes work between AP, ALC, and some ALP (the more advanced classes). Cross-Fit is primarily the “Power Endurance” concept of ACC and AAP. The High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is the concept of maximizing the “fat burning zone” – primarily in the ALP to AAC zones. As previously stated, all of these are effective. However, like anything in the fitness world – it’s always best to think in terms of overall periodization and building blocks.

Of course the ultimate “fat burning zone” lives in ALP and ALC. Hence why you see the overall breakdown of the BPS Zone microcycle feature more than half of the overall volume within ALP and ALC. However, if you want to maximize the efficiency of each zone, you have to be efficient in all zones.

Implementing the Zones into a Specified Mode

This is where it gets interesting – motivating and coaching the clients to express the proper intensity in the assigned Zone. Specifically the most challenging will be to train at maximal or near-maximal intensity in the Alactic Zones. Note in the chart many of the AAC and AAP are very short bursts with a work to rest ratio assigned as in the chart above.

An example is Week 1, Day 1. Note it’s a Concept 2 Row machine with a work to rest ratio of 15 sec on and 45 sec rest (in this case, recovery). This is near-maximal intensity (basically go as hard as possible) is for 15 seconds. Then keep rowing, but go at a lighter intensity and slower pace for 45 seconds. Then continue to repeat these intervals for a given amount of time (as stated below in the breakdown – 10 minutes for beginners, and 15+ minutes for advanced. The key is to execute maximal intensity during the 15 seconds each bout for the entire duration of the workout. Obviously if your executing 15 total bouts, the first 15-second bout (maximal) will be more intense than the fifteenth 15-second bout (near-maximal). However, your intention is to move the row as fast as possible; even though the power output might be near maximal.

All of the intentions that need to be reflected by a specific intensity are shown in the chart (low, 40%, 50%, 60%, 75%, 100%, etc).

Heart rate monitors are an excellent mode to measure intensity and recovery over time – and should be recorded. For example above, the first time the 15s/45s system is performed, it will get the heart rate to a certain high percentage of max heart rate. And there will be a certain time that it takes the heart rate to get back down to resting at the completion of the workout. If this is 15s/45s is repeated at a later time, and it’s compared to the first workout:

- More intensity should be executed for the 15s work bouts for the second workout

- This increased intensity should be able to be done at a lower heart rate during the second workout (even though it will still be a high percentage of max heart rate)

- The heart rate recovery will get back down to resting quicker after the second workout

Just like any style of training – records of progression is the key to ensure proper overload without overtraining.

The Monthly Breakdown

- Microcycle – one month (4 weeks)

- Approximate training volume – 3 days per week

- 12 total workouts

- Workout length

- Beginner – 10 min Zones, 20 total minutes per day

- Advanced – 15-20 min Zones, 20-40 minutes per day

- 1-2 hours per week; 4-8 hours per month

- Two Zone segments per workout

- 24 total Zone segments per month breakdown

- AP – 2 total Zones

- AC – 2 total Zones

- ALC – 4 total Zones

- ALP – 8 total Zones

- AAC – 6 total Zones

- AAP – 2 total Zones

The Variations

The first thing to consider is the equipment and space you have access to. In an ideal world, you want to provide as much variety as possible. The variety should be machine based and non-machines. Machines can be very effective, as many machines greatly reduce joint loading (overall efficiency without overtraining and/or unnecessary wear on the joints). However, movement patterns can greatly enhance the overall intensity of the zone.

Notice that in the BPS rotation system, there are about 5 different categories of “machine” based modes:

- Run – treadmills and specialized treadmills

- Step – Versaclimber, Stairmaster, Stepmill, Box Stepups

- Stride – Cybex Arc, Eliptical

- Row – Water, Concept2

- Bike – Upright, Recumbent, Spin

There are also 5 different classifications for Non-machine based modes:

- Movement – intervals of speed, footwork and agility

- Resisted SPE (Strength/Power endurance continuum) – DB, KB, Sled

- Variable Load – Bands, Air Resisted (Keiser)

- RNT – Reactive Neuromuscular Training with MB, Battle Ropes

- BW and Suspension – body weight exercises in place or slow moving (like squats and lunges; Suspension Training (TRX)

Note in the chart, there is a frequency of total number of times in the given month microcycle. Each mode classification will be 2-3 times in the month. Consistently CHANGING THE STIMULUS will have a tremendous impact on getting clients to exceed a training plateau. It also keeps peaking the interest levels of clients because workouts will not become stale. However, it’s also extremely important to keep in mind that clients have to get better at a specific mode of stimulus. Don’t change the mode too often that they can’t actually show improvement.

The Final Step of Advancement – Incorporating Strength and Power

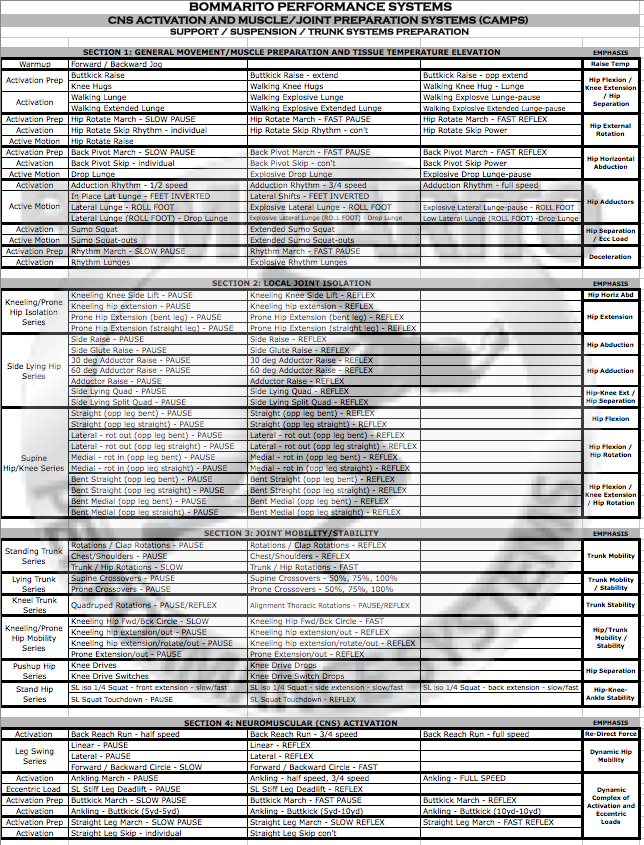

This is really the most important step, especially for any clients or athletes that are above the beginner level with regards to training. As there are 6 different energy systems, there are also 6 different variations of strength and power with regards to resistance training. It should be periodized as the ESD systems into a given microcycle. And, most importantly – it should be incorporated immediately after the ESD cycle. So a given day might look like this for the advanced client/athlete:

- CAMPS – 5 min

- ESD Zone1 – 10min

- ESD Zone2 – 10min

- Weight Room Zone 1 (Primary Complex 1) – 15min

- Weight Room Zone 2 (Primary Complex 2) – 15 min

- Auxillary Strength Complex – 5 min

In addition, consistently rotating between the “big 6” in the weight room:

- Absolute Strength

- Stabilizing Strength

- Strength Endurance

- Speed Strength (and all of its components to build the base of Power)

- Power Endurance

- Power

Note that some of this is addressed in the “Cardio ESD Zones” outside of the weight room like SPE (strength endurance and power endurance continuum with KB, DB, and/or Sleds). However, it needs to be addressed in the weight room as well – just not on the same day.

The great thing about this style of “back-to-back” type of workouts is that you elicit fat burning enzymes by working in specific ESD Zones. Once you stimulate this type of response, you weight room work will be much more efficient, in addition to the fact that you will continue to burn fat in the weight room portion. You will also prep the tissue much more efficiently during the ESD zones that will have a tremendous benefit in the weight room portion. As always, don’t think of it as a “warm-up”. Think of the CAMPS and ESD zones as stimulating the CNS, increasing the threshold for absorbing and re-directing force, and raising tissue temperature – all of which will make the weight room sessions more efficient.